Amidst the nightmare of the pandemic, there is one small, special gift to law firms: a swift kick up the backside on remote and flexible work.

A year ago, it would have been difficult to imagine a whole team being allowed to work remotely, let alone a whole office. And yet lawyers have proven their resilience; despite no time to plan or test, most firms made the forced transition to remote work successfully. Many were so successful they’ve decided to retain widescale remote and flexible work practices after the pandemic.But while this is a good start, we think firms are missing an opportunity. Instead of asking whether to keep remote and flexible work practices, firms should be asking themselves this question:

How do we create the right environment for our people to do their best work?

In 1922, psychiatrist Carl Jung had a problem. He’d just published Psychological Types, the book where he first dared to publicly disagree with his mentor, Sigmund Freud. It was a dangerous move at a time when Freud was hailed as the indisputable king of psychology. But it was the first step toward Jung’s dream of changing the way we understand the human mind. To achieve this, he’d need to quickly write a series of further articles and books establishing and defending his views, while also maintaining his lecture circuit and busy counselling practice. And he’d also still need to find time to immerse himself in Zurich’s coffeehouse culture, where he could hone his ideas with some of Europe’s greatest thinkers (including Einstein, who discussed his theory of special relativity with Jung over several dinners).

Even though Jung faced this conundrum nearly a century ago, the parallels are startling similar. To become one of the most respected thinkers of the 20th century, Jung needed to juggle deep work – something best done in solitude – with his client service obligations. He also needed a social environment to invite the serendipity and collaboration so many firms have chased by moving to open offices.

So how did Jung solve this problem?

The answer: he built a house he called the Tower in a small village named Bollingen. It had meditation rooms and a private office where he could lock the door. He spent several months every year locked in the Tower where he concentrated on writing and creating without interruption. And then for the rest of the year, he threw himself into the busy world of Zurich: lecturing, seeing clients, and meeting fellow intellectuals.

Jung’s solution is echoed today in many executives – including Bill Gates – taking the time for deep work retreats in between normal office work. It’s also echoed in the viral, brilliant essay written by hacker philosopher and investor Paul Graham on the difference between ‘Maker’ and ‘Manager’ schedules.

It’s not practical for everyone to disappear for months at a time. But nor is it necessary. Jung could not telecommute as we can today. How would he organise his time now, 100 years later, if he had our technology? We’d bet good money he would use it to shape where and how he worked.

There are two crucial lessons for law firms here.

The first is that strategically thinking about and designing our work environment can dramatically improve our work: the quality, the productivity, and yes – the satisfaction.

The second is to recognise, institutionally and individually, that different work requires different ways of working.

It’s time to dream

This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for firms to ask two seemingly simple but overwhelmingly powerful questions: how do we do our best work, collectively and individually? And how can we create the best environment to ensure our lawyers get as many ‘ideal days’ or ‘ideal hours’ of work as possible?

Let us be clear. This is not about feel-good, self-help, faux-employee-nurturing-lip-service.

This is about honest-to-goodness, authentic, productivity-enhancing, profitability-growing, revolutionary changes which we get to make now and over the next few years – starting almost entirely from a blank slate.

We all know this remote work experiment would never have happened but for the pandemic. But does everyone understand the range of choice we have before us?

We could just let a few more people work from home than we used to.

Or we could radically reimagine what it means to work in the office and redesign the way we work to do so much more than we have done before.

Managed distributed work and radical office space

Here is our vision.

We believe it’s possible to allow people the freedom to be part of a remote and distributed workforce and come into an office when it makes sense to do so. We also think there are answers outside of the traditional CBD office and that some of our ideas might surprise you.

Sound simple? But yet, like many things, it’s the implementation that’s hard. Because the system needs to be designed for the benefit of all, not just the few. It must work for clients, lawyers, partners and support staff. Lawyers cannot get the absolute freedom to dictate when and where they work. That’s why we call it ‘managed’ distributed work: firms can only transform how they work and reap the benefits of that transformation if they invest in the work of managing both people and place.

That work starts with three critical steps:

1. Analysing what we need as lawyers.

2. Investing in the right resources.

3. Facing our fears of remote, flexible and distributed work.

— STEP ONE —

Analysing what we need as lawyers

There’s endless commentary about what remote work and office space looks like in a post-COVID world. A lot of it plays on the natural fears people have about change. Very little of it helps us solve the problems that none of us chose to have. As a result, it seems much easier for us to put our heads down and just keep working the same way we have since the pandemic began. To settle for a little change, rather than transformative change.

But to answer our opening question – how do we create the right environment for our people to do their best work? – we have to think bigger.

There are those who believe collaboration can only occur in the office, and collaboration is good, so therefore we must have offices (more on this in Part 2). Others are concerned that junior staff and new starters can’t be trained properly remotely, which will reduce effectiveness and profitability. And many are afraid that losing the office means losing the team, losing the culture, and losing the special something that makes us great.

In the opposing anti-office camp, there are any number of Dilbert cartoons (and scientific studies) arguing the view that the modern office isn’t conducive to focussed work. Some might even say nothing good happens in offices at all, and everyone will be better off when they are done away with forever.

We could pick a side and argue the toss. But we believe lawyers should take a more nuanced approach. To move beyond loaded, black and white viewpoints. We need to find answers for ourselves and our profession and not tie ourselves in knots trying to apply the truisms of other industries to ours. And the way to do this is to ask the real questions for lawyers:

Firstly, what do lawyers do? Not engineers, not software developers, not accountants. Lawyers.

Secondly, of the things lawyers do, how many of them need (or substantially benefit) from in-person contact?

Thirdly, of the things which remain, which ones need the office itself, and not another location or venue?

Fourthly, of the things remaining which really do require the office, how do we best organise ourselves around them?

Only once you have the answers to these questions can you work out how much time people need to spend together to do their job well, and how much of that time requires the office. You can then determine how much office space you need, when you need it, and how you can properly manage and maximise the benefit of that space.

Here’s an example: if you determine that less than 20% of your team’s time is spent together, you could mandate a single day per week when all team members must be present. Everyone can then work around this fixed point, which also creates the perfect hub for regular team meetings and social events like team lunches and morning teas. If there’s an ongoing need for two teams to work together, they could be scheduled for office time on the same day.

Or maybe your team doesn’t need to see each other once a week. Maybe you find they work best with quality time together once a month, or deep time every 6 months. Of course, teamwork isn’t the only consideration. You’ll need to look at time you want to spend face-to-face with clients as well, and ensure there’s sufficient coverage every day of the week – wherever it’s needed – so both external and internal clients are always serviced.

That’s the point of managed flexible work: it isn’t set by individual fee earners and their various life preferences. There is no excuse for instance for every senior lawyer to have their day off on a Friday. If necessary, Fridays can be rostered rotating days off, or based on a yearly roster to account for childcare. It’s a privilege to have flexibility, and it requires flexibility on both sides.

— STEP TWO —

Investing the resources to make it work

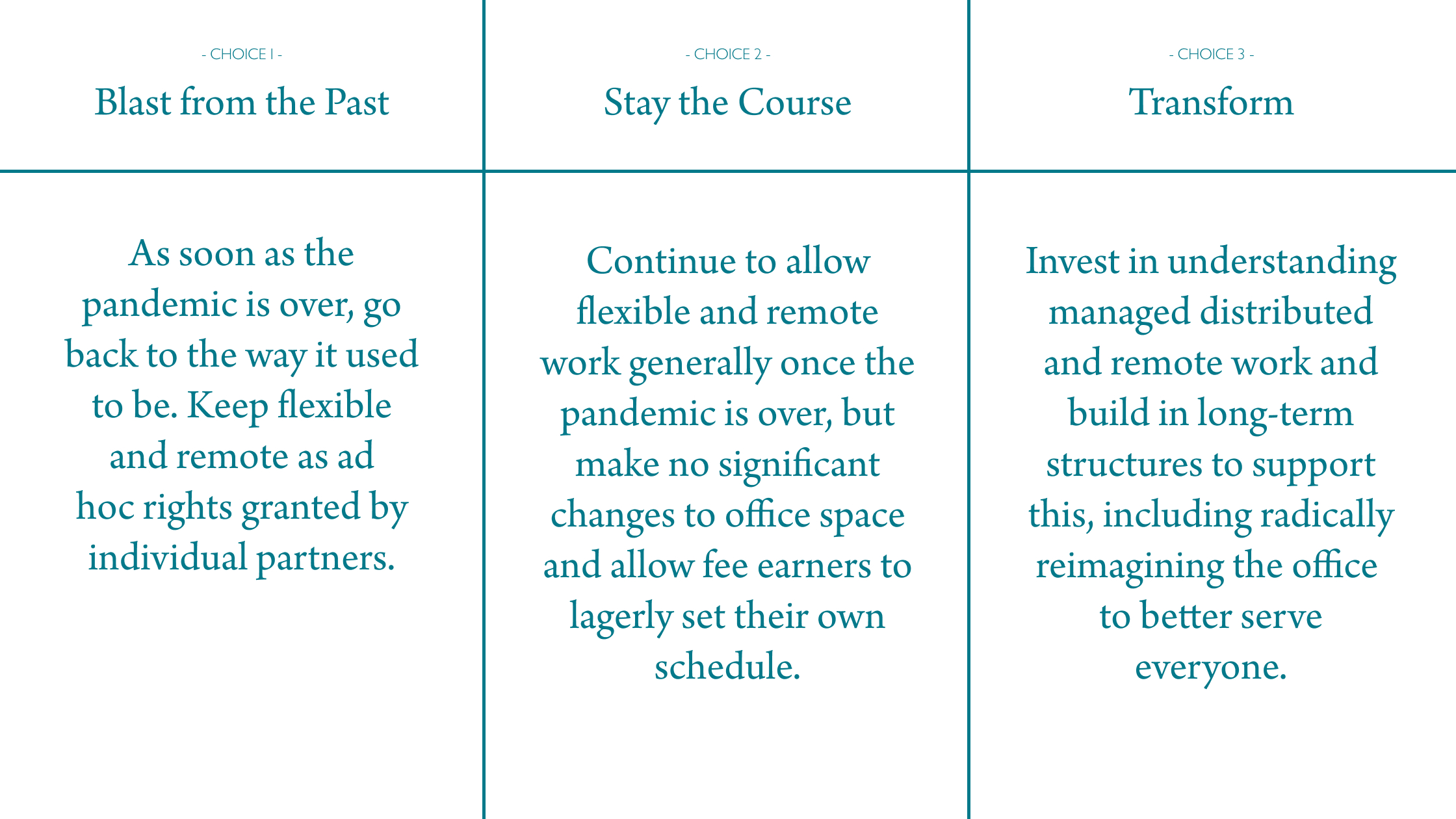

If all this tailoring sounds like a fair bit to manage… it is. There is a cost to transforming how law firms work. And yet this investment is absolutely critical. Because firms have three choices facing them.

Given many firms have announced they are embracing continued remote and flexible work practices long-term, we think Choice 1 is a dead end. Even before the pandemic, flexibility was one of the top priorities for many lawyers. If some firms force their lawyers back into the office full-time while the majority allow flexibility, many lawyers will jump ship.

Choice 2, however, is also problematic. Allowing flexible and remote work to evolve organically without taking control of both the work and the space is dangerous. As we explore in Part 2, collaboration matters. Trust matters. Culture matters. If firms allow lawyers to make free choices about where and when they work without an overarching firm strategy, it is very likely that firm performance will suffer. And if firms fail to manage ‘where and when’, they will fail to capitalise on new efficiencies and better effectiveness.

That’s why we want to talk about Choice 3. This choice will transform how people work and what the office should look like. It will be radical, reformative, and give progressive law firms a clear advantage over more cautious competitors. But it will also require firms to truly learn how and where they do their best work, and face their fears of change.

— STEP THREE —

While the pandemic has destroyed many myths around remote and flexible work in legal practice, we need to acknowledge that many lawyers and law firms are still afraid. Afraid that, without the central hub of a physical office, productivity and teamwork will suffer in the long term. Afraid that managing a distributed workforce will be too hard, too costly, or both. Afraid that reducing office space will reduce prestige. Afraid that they’ll realise too late they made a mistake. Not to mention, afraid that they aren’t equipped to manage such mammoth changes.

To be clear, these are all justifiable concerns. But that doesn’t mean firms should throw up their hands and stick with the status quo. Or let their fears hold them back, leading to half-hearted changes doomed to failure before they start. The answers are either already out there, or we’re fully capable of finding them out ourselves.

After all, we’re lawyers. We need to have more faith in ourselves to solve our own problems. Our job is to unflinchingly identify and understand risks so we can better manage them. We need to apply that skill-set to this problem, because without it, firms can’t make good, clear decisions around what we actually need and how to invest our resources. It’s these fears that have kept alive so many of the myths around why firms need an office … and have also prevented firms from building their own version of Jung’s Tower: perfect spaces designed to help everyone do their best work.

That’s why in Part 2 of this article, we’ll dive further into the myths behind why we as lawyers need the office, so we can design the office to benefit how we actually do legal work. Stay tuned. In the meantime, sign up below to get a free copy of our whitepaper when it drops: ‘Getting the Best Work from the Best People – a Self Help guide for Law firms on Managing Flexible Teams’.

Choice 2, however, is also problematic. Allowing flexible and remote work to evolve organically without taking control of both the work and the space is dangerous. As we explore in Part 2, collaboration matters. Trust matters. Culture matters. If firms allow lawyers to make free choices about where and when they work without an overarching firm strategy, it is very likely that firm performance will suffer. And if firms fail to manage ‘where and when’, they will fail to capitalise on new efficiencies and better effectiveness.

That’s why we want to talk about Choice 3. This choice will transform how people work and what the office should look like. It will be radical, reformative, and give progressive law firms a clear advantage over more cautious competitors. But it will also require firms to truly learn how and where they do their best work, and face their fears of change.

— STEP THREE —

Facing fears of remote, flexible and distributed work (and reimagining the office)

While the pandemic has destroyed many myths around remote and flexible work in legal practice, we need to acknowledge that many lawyers and law firms are still afraid. Afraid that, without the central hub of a physical office, productivity and teamwork will suffer in the long term. Afraid that managing a distributed workforce will be too hard, too costly, or both. Afraid that reducing office space will reduce prestige. Afraid that they’ll realise too late they made a mistake. Not to mention, afraid that they aren’t equipped to manage such mammoth changes.

To be clear, these are all justifiable concerns. But that doesn’t mean firms should throw up their hands and stick with the status quo. Or let their fears hold them back, leading to half-hearted changes doomed to failure before they start. The answers are either already out there, or we’re fully capable of finding them out ourselves.

After all, we’re lawyers. We need to have more faith in ourselves to solve our own problems. Our job is to unflinchingly identify and understand risks so we can better manage them. We need to apply that skill-set to this problem, because without it, firms can’t make good, clear decisions around what we actually need and how to invest our resources. It’s these fears that have kept alive so many of the myths around why firms need an office … and have also prevented firms from building their own version of Jung’s Tower: perfect spaces designed to help everyone do their best work.

That’s why in Part 2 of this article, we’ll dive further into the myths behind why we as lawyers need the office, so we can design the office to benefit how we actually do legal work. Stay tuned. In the meantime, sign up below to get a free copy of our whitepaper when it drops: ‘Getting the Best Work from the Best People – a Self Help guide for Law firms on Managing Flexible Teams’.